Warning: this post contains references to trauma, abuse and neglect

If we were to go back to 1970s London and a Queen concert, we might find a man in his 20’s trying excitedly to get backstage after the encore. The young man is from India and was a school friend of the lead singer Freddie Mercury. They haven’t met since they were 16. He can’t wait to see Freddie’s face when he greets him. He makes it to the dressing room. There are a lot of people around. When the man finally gets face to face with his famous school friend, ‘Bucky’ Bulsara, he gets a shock. He will later tell another school friend Gita what happened: “Freddie just looked right through this poor fellow and said to him ‘I’m sorry but I’m afraid I just don’t know who you are’. That was when we all knew for sure that he wanted nothing more to do with us. The past was something he was determined to leave behind”1.

In part A, we began a long journey from Stone Town, Zanzibar, to Panchgani near Mumbai, where a young Farrokh Bulsara was sent to boarding school. But I started with Queen on stage at the 1985 Live Aid concert – a historic charity event staged to raise money for Ethiopians trapped in a famine. Freddie had taken his partner Jim Hutton with him. The fact that it was the first concert Jim had ever been to must have compounded his experience that day as he stood in the wings watching Freddie Mercury – or as Freddie called his stage persona “big Freddie”. When Jim had met Freddie, he didn’t know he was a star. And now here was his partner giving the performance of his life. And here was the audience singing along as Freddie concluded (and the evidence was in front of him), ‘we are the champions of the world’.

Bombay to Poona by train

Now we are nearing the end of the 3000-mile journey to Panchgani, where Freddie was to stay at boarding school. From the port city of Bombay (as it was then called) a train took him with his mother to Poona.

The adult Freddie always avoided the subject of his childhood. But on one occasion he made some striking statements in response to questions directly about boarding school abuse. The interview with Julie Webb can be found in an old copy of the UK’s New Musical Express from December 3rd, 19742. Here is an excerpt, left as it was published, in the language of the day which has changed so much:

‘Boarding school… if we are to believe stories that circulate about boarding schools – brutish behaviour, homosexual goings-on – well, the mind positively boggles in Freddie Mercury’s case.

I broach the subject…

Freddie: “it’s stupid to say there is no such thing in boarding schools. All the things they say about them are more or less true. All the bullying and everything else. I’ve had the odd schoolmaster chasing me. It didn’t shock me because somehow boarding schools… you’re not confronted by it, you are just slowly aware of it. It’s going through life.”

So was he the pretty boy who everyone wanted to lay?

Freddie: “Funnily enough, yes. Anybody goes through that. I was considered the arch poof.”

So how about being bent [sic]?

Freddie: “You’re a crafty cow. Let’s put it this way, there were times when I was young and green. It’s a thing schoolboys go through. I’ve had my share of schoolboy pranks. I’m not going to elaborate further.”’2

Till his death, Freddie did not elaborate much further. But I think this is enough. Part of me feels apologetic quoting this 50-year-old interview. It feels like deep water. No deeper though, perhaps, than Monroe and Brando who were also abused within institutions (and both, it seems, were scapegoated). Both later found temporary relief in iconic fame. For me, as a psychologist, there are some striking aspects of this conversation beyond the implied events of Freddie’s childhood at boarding school. There is something Freddie is doing in this interview in 1974 whilst disclosing these events. He generalises and manoeuvres me as a reader to not face the specifics that are nevertheless actually here. “Funnily enough…anybody goes through that”. Wait. No, they really don’t. I wonder if Freddie is again smoothing something over.

I am not saying this to be critical of Freddie. I am suggesting that he had found a way to minimise experiences that deeply impacted him at a highly vulnerable time. We are talking about traumatic memories. He has found a way to distance himself from feelings which would perhaps overwhelm him if he didn’t. And verbally, there is an intelligent sleight of hand that helps both Freddie and also the reader (and Julie Webb) to be unimpacted. The facts are sanitised. Yes, he learned how to “look after himself”. And here as an adult, he is artful in not asking for compassion. In narcissism we hear a lot about the lack of empathy for others. In this interview we can hear the less talked about side of this lack of empathy - emotional distance from self. Because it would be unmanageable. This, for Freddie, is what ‘looking after himself’ as an adult looks like. Another strategy for finding distance from vulnerability was more visible than this. It was, of course, to ruthlessly seek an admired, emotionally distant and all-powerful role for himself.

On the map of narcissism we find these two strategies. The first is to be emotionally dismissing and distant – from others but also from self. On the map of narcissism (see below), the lower ‘dismissed’ role could be played by others in Freddie’s life but also by Freddie’s own feelings – feelings now buried by himself. The second is what we see at Live Aid. He is not avoiding all emotions – it’s ok to feel specifically like a champion.

The map of narcissism3*

Ryle’s map of narcissism suggests that vital ingredients for narcissism to develop are overwhelming condemnation and a pattern of dismissing of the child’s emotional needs. Outright abuse is not a necessary ingredient for narcissism to develop. But as I explore the childhoods of the iconically famous, I am finding that outright abuse is far too common to be a coincidence. Of course, where there is abuse, there is sadly often also condemnation (or a sense of condemnation even where it was not intended) and sadly where there is abuse there is also often emotional neglect. Farrokh was put in an emotionally acutely vulnerable position for most of his childhood.

Simon Napier-Bell is one of the most famous managers of pop stars in UK music history. His clients included Ultravox, Marc Bolan of T-Rex, Sinead O’Connor, Wham and George Michael. I expect that he never read about narcissism theory. But from his own experience he made a bold statement: “being an artist is a cry for help…Artists always have an abusive childhood – at least in terms of emotional deprivation. So, they have this desperation to succeed, to get love and attention.”1

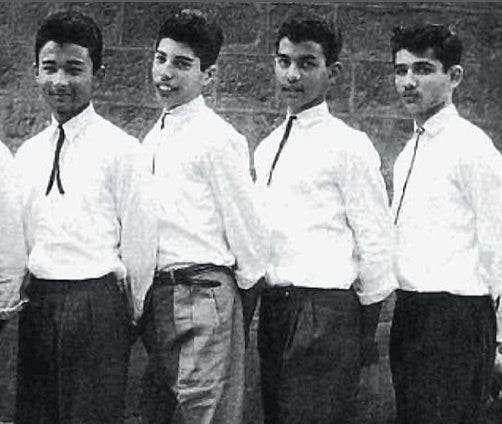

The Hectics were a school music group in which teenager Freddie Bulsara played piano.

From Poona, near Bombay (as it was then called) there was a short journey by bus to Panchgani.

For Freddie, as he was called by the time he left boarding school, there was this distance from home, on top of bullying, on top of abuse. But then, there was condemnation. A maths teacher recalled that Freddie’s sexual activity was “already well known within the establishment…His father would have been informed and I’m sure was very disappointed.”4 This sounds like he faced judgment and condemnation first from school bullies, then from the institution and finally from his family in Zanzibar. Their own faith described homosexual activity as a kind of demon worship4 and Zanzibar’s majority Muslim culture also condemned it. After travelling back 3000 miles, what reception would await the 16-year-old Freddie?

If Freddie’s experiences at this school were less harmful than this, then we would have to explain a few puzzling facts. Farrokh’s parents invested heavily in their only son having a good education in India. But despite this debt to his parents, Freddie left the school early, before year 11, having failed his class 10 exams. He was leaving with no qualifications and would attempt to finish his schooling in Zanzibar – the very thing his parents had made a huge sacrifice to avoid. What had caused this failure? From now on, despite showing intelligence as a young boy, and throughout his life, he struggled with sustained concentration and the demands of academic study, including at his London art college. As the lead singer of a band in which the other members had strong academic backgrounds, his publicist once fabricated a list of Freddie’s own qualifications. The collapsing of academic potential including the ability to concentrate can be a consequence of trauma.

Secondly, Freddie found success beyond the wildest dreams of his close-knit family and school friends. Some had cheered him on in his school days music group The Hectics. When he became famous, Freddie blocked them all out. For the rest of his life.

By the time Freddie’s final partner Jim Hutton visited his parents’ house (under the guise of being Freddie’s chauffer), he had already stood backstage at 1985’s Live Aid concert. Clearly Freddie’s parents would be proud of their son’s achievements in music – even if his sexuality could not be spoken about. But as Jim spent time in the house, one thing gradually came into Jim’s awareness: there were no photos of their megastar son. None. The walls of their London house spoke volumes of something. DJ Simon Bates interviewed Mercury in 1985 but there were two conditions: it must take place in Queen’s own offices and “no questions about his parents were permitted.”4 How would we know if he was actually angry with his mother for abandoning him at the age of seven? Perhaps he would have let her find out he had AIDS from the TV news, 24 hours before his death. This must have been a humiliating way to be told.

Bohemian Rhapsody is Freddie’s masterpiece – with lyrics he had written alone before presenting the idea to the band. When asked about the lyrics he said, “I think if I were to get into every word, it would be very boring for the listeners, and it might also shatter a few illusions. I write complicated songs”5 But here is this sleight of hand again – a world in which “shattering” is “boring”.

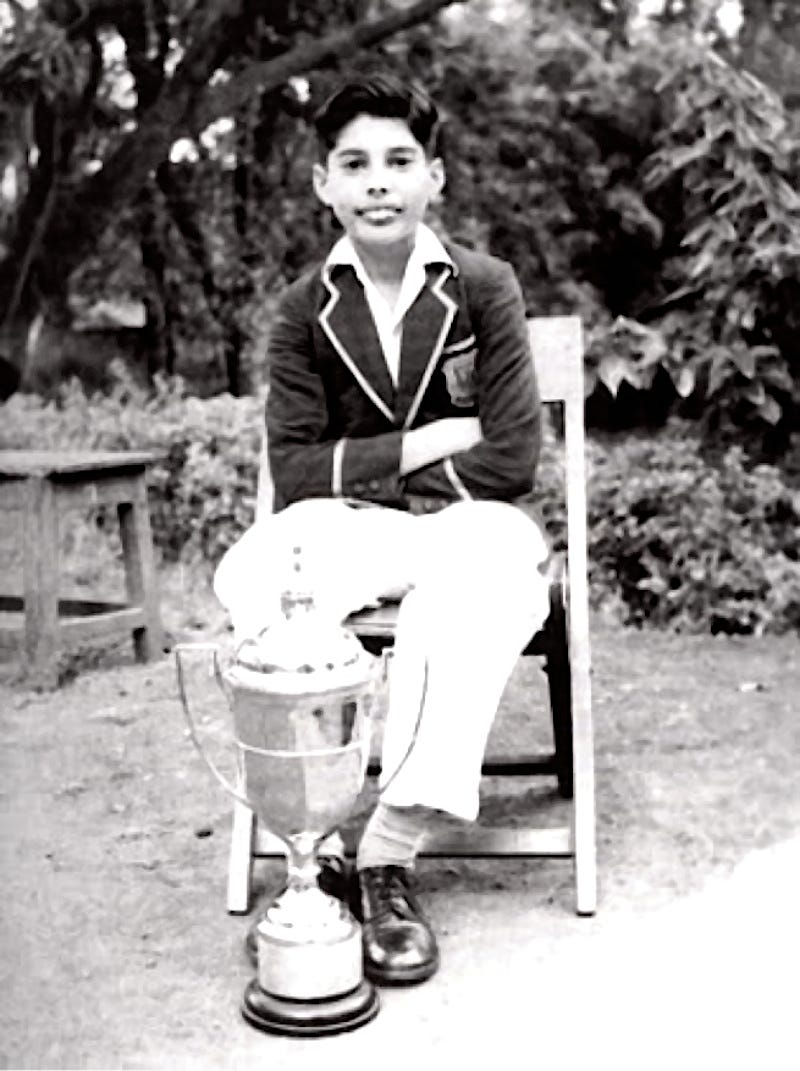

Freddie Bulsara at boarding school

Bohemian Rhapsody is a complicated song. Some think that ‘Mama’ refers to Mary Austin his first serious adult love affair. Most commentators have concluded that it is Freddie wrestling with his culturally unacceptable sexuality. His orientation is in any direction the wind blows – ‘easy come easy go’. Music critic Anthony Curtis listening to the lyrics heard it as a coming out song: “I’m being punished – at the same time that there’s this desire for freedom.”4 But what if there were references to a poor boy whose life had just begun? What if there is in the song a mother who has abandoned and killed off the man who would have been; a woman who loved a boy and then left him to die? What if this mother in the song later condemns him – whilst those of his community also do so ‘bismillah’ – in the name of Allah. Does this sound like the condemning voice of London or of Muslim majority Zanzibar?

Freddie may, in the song, have been wrestling with his adult sexual identity in a homophobic 1970s Britain. But he may also have been struggling with a whole childhood ‘monstrosity’ of abandonment and abuse that would remain unspeakable. Except perhaps in a song. And even in this private, six-million selling, song he will smooth it over. And so, we the listeners can feel as if, to him, it doesn’t really matter.

Bohemian Rhapsody

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

Caught in a landslide, no escape from reality

Open your eyes, look up to the skies and see

I'm just a poor boy, I need no sympathy

Because I'm easy come, easy go

Little high, little low

Any way the wind blows doesn't really matter to me, to meMama, just killed a man

Put a gun against his head, pulled my trigger, now he's dead

Mama, life had just begun

But now I've gone and thrown it all away

Mama, ooh, didn't mean to make you cry

If I'm not back again this time tomorrow

Carry on, carry on as if nothing really matters

Too late, my time has come

Sends shivers down my spine, body's aching all the time

Goodbye, everybody, I've got to go

Gotta leave you all behind and face the truth

Mama, ooh (any way the wind blows)

I don't wanna die

I sometimes wish I'd never been born at allI see a little silhouetto of a man

Scaramouche, Scaramouche, will you do the Fandango?

Thunderbolt and lightning, very, very frightening me

(Galileo) Galileo, (Galileo) Galileo, Galileo Figaro, magnifico

But I'm just a poor boy, nobody loves me

He's just a poor boy from a poor family

Spare him his life from this monstrosity

Easy come, easy go, will you let me go?

Bismillah

No, we will not let you go (let him go)

Bismillah

We will not let you go (let him go)

Bismillah

We will not let you go (let me go)

Will not let you go (let me go)

Will not let you go (never, never, never, never let me go)

No, no, no, no, no, no, no

Oh, mamma mia, mamma mia

Mamma mia, let me go

Beelzebub has a devil put aside for me, for me, for me

So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye?

So you think you can love me and leave me to die?

Oh, baby, can't do this to me, baby

Just gotta get out, just gotta get right outta here

Ooh

Ooh, yeah, ooh, yeah

Nothing really matters, anyone can see

Nothing really matters

Nothing really matters to me

Sometimes, the drive for fame is powered by a need to find maximum distance from vulnerability, because it has been intolerably unsafe. If we were to return to London in 1985, and the Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium, we would find on stage Freddie Mercury fronting Queen. He is here to raise money for Ethiopia. But his performance will be seen as the pinnacle of his career. We see tragic images on the stadium’s huge screens of vulnerable, African children. Freddie Mercury himself could not be any more different from these images. He is here to save these children with this performance of his life. He carries a persona that electrifies the crowd – one fist in the air and another gripping his half mic stand. This is the persona of a champion: he is powerful, invulnerable and worshiped. Invisible and forgotten, so that the entire crowd are unaware, is the boy he doesn’t talk about in interviews. Invisible here is Farrokh Bulsara, a lonely, abandoned, vulnerable, African child.

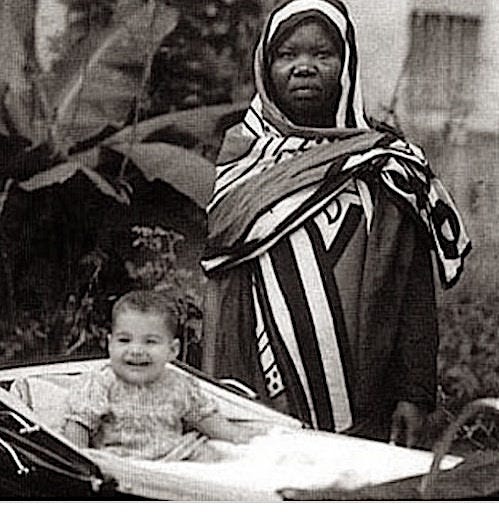

Baby Farrokh in Zanzibar with his nanny, Sabine (1947)

Disclaimer: All views expressed are my own unless otherwise stated, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution I have been employed by. The content here is for information and should not be interpreted as advice.

*Ryle did not apply this approach only to narcissism. If this mapping approach has been used in your own therapy, this does not mean that you have narcissistic difficulties.

Notes

Jones, L-A (2012). Bohemian Rhapsody: The Definitive Biography of Freddie Mercury. Hodder.

Webb (1974) Highly Strung? We fight over hairspray! New Music Express. December 3rd, 1974.

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I.B. (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Wiley.

Richards, M & Langthorne, M. (2016) Somebody to Love: The Life, Death and Legacy of Freddie Mercury. Blink.

Mercury, F. (2019). Freddie Mercury: A Life, In His Own Words. Independent.

Fabulous writing! Thank you for sharing this about Freddy. There are so many things I didn’t know.