Warning: this post contains references to trauma, violence, abuse and neglect

Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca (1942)

Casablanca was made in 1942 at the height of the film noir genre, and yet references to the film are found often in modern culture. In La La Land (2017) Emma Stone’s character is obsessed with the film. Ocean’s Eleven (2002) quotes “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine”. “Round up The Usual Suspects” inspired Bryan Singer’s film, The Usual Suspects (1995). Woody Alan made Play it Again, Sam (1972). Lines such as “here’s looking at you kid” and “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship” are still in modern circulation. Also iconic, in Casablanca, was the lead character: a cool, jaded man with a raspy voice making difficult choices between head and heart and taking solace in Sam’s piano. The character’s name was Rick Blaine, played by Humphrey Bogart.

On a list of the greatest American movies of all time in 2007, four Bogart films appeared, with Casablanca ranking third. Journalist and presenter Alistair Cooke said of Bogart’s breakthrough film, The Maltese Falcon, “You could see everything in his face. The camera loved Bogie. He was born to be in films…He had become what a star had to be, a genre unto himself.”1

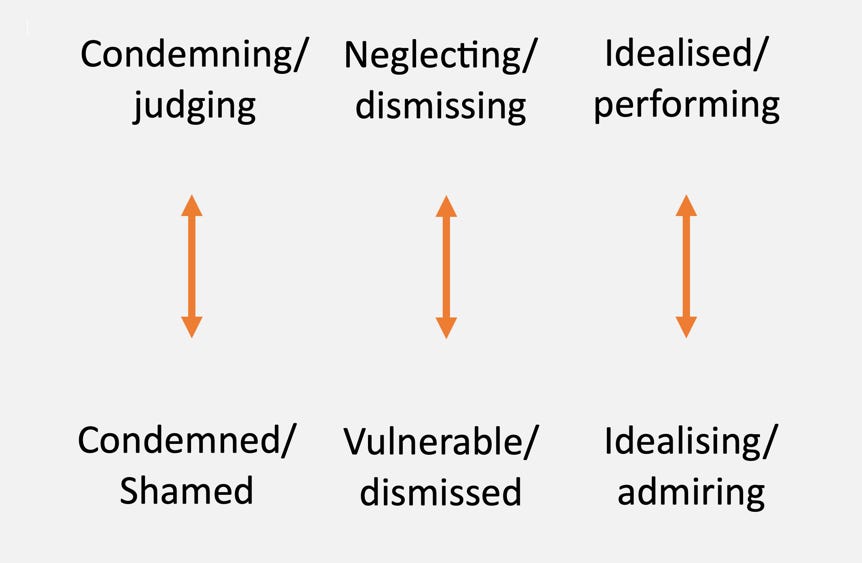

I am writing about the iconically famous to see what their lives can tell us about narcissism. Why should the iconically famous necessarily be narcissistic? Because there is a performance face of narcissism (see post about this). The map of narcissism (below) describes both the adult strategies that combine to characterise narcissism, and the childhood experiences which provoke these strategies early on in life.

The map of narcissism2*

When I started reading about Humphrey Bogart, I realised that he might help answer a question that has come up in comments on this blog. It goes something like, “how can we say that narcissism is caused by childhood trauma, when we can see extreme narcissism including perpetrator behaviour in adults who have had a comfortable upbringing?”

If we were to go back to the first year of the 20th century, and a New York restaurant called Luchow’s on 14thStreet, we might find Dr Belmont Bogart dining with friends. During the conversation he says something about his newborn son, that places him immediately in a higher socio-economic circles of US society: “My wife says Columbia, but I definitely see the boy as a Yale man.”3 Bogart had what some would call a good start in life. His mother, by the time he was a teenager, had perhaps the largest salary of a professional woman in the US: $50,000. His father was a cardiopulmonary surgeon with a prestigious patient list. It would be through family connections that Humphrey would get some of his jobs as he navigated his adult life. And it was through a family connection, Bill Brady Snr that Humphrey would get into the theatre and eventually the film business.

It is not difficult to paint a picture of Bogart as a young man from a wealthy background who disappointed his parents, dropped out of education and got into a lot of trouble, before falling into acting partly through some privileged family connections. If Bogart’s iconic performances reflected narcissism, how do we square this with a comfortable upbringing? The map of narcissism I am using refers to specific patterns of difficult childhood experience. In part B, we will look deeper into his childhood. First, we need to ask another question about the adult Humphrey Bogart. If his charisma and talent did reflect narcissism, were there other adult strategies for managing himself emotionally and his relationships, that are also named on the map of narcissism?

The flight from feeling

On the map of narcissism, we find an adult strategy of maintaining emotional distance. This is thought fundamentally to be a disconnection from the emotional self. But what gets noticed more is a consequence of this: a lack of emotional empathy for others.

If we were to go back to 1951, and March 12th at a Los Angeles airport we might find actor Humphrey Bogart and his wife Lauren Bacall boarding a plane. Bogart, now a famous actor, is going to shoot the film The African Queen, in Congo, for which he will win an Oscar. Lauren is going to accompany her husband. They will first fly to New York, with a stopover in Chicago, before boarding a cruise to London at the start of a four month round trip. On the tarmac, their two-year-old first born, Stephen, watches the airplane taxi away for take-off. Little Stephen will be looked after by Mrs Hartley his nurse maid – a large woman who on the tarmac holds the toddler tight in her arms. As the plane takes off and begins to climb, Bogart and Bacall start to relax. Behind them, and thousands of feet below, Mrs Hartley the nurse maid, with no warning, has a heart attack and dies instantly.

Little Stephen is unhurt physically and others are present to take him away. At Chicago, Bogart and Bacall receive a call and are informed about the death on the tarmac. Bacall’s mother has the child. Bacall wonders whether she should go back. She speaks to “Stephen’s doctor’ by phone and is reassured that they will find another nurse who is acceptable. Bogart and Bacall will stick to their four-month schedule in Africa – which will run over a little1. Bacall will later tell her adult son, “I tried to talk to you Stephen, but you refused to speak to me. I talked to your doctor again. He told me you would be fine. There was never any issue of your physical needs being taken care of.”1

I found this account very sad to read. Bogart’s rationale for this decision, which would have been made jointly, is not recorded. 35 years later little Stephen will write a book grappling with the childhood he had, leading as it did to drug addiction, relationship failures and a difficulty finding his place. He won’t ask why his nurse dropped dead on the tarmac. He will ask a more basic question: “why didn’t you come back?”1

It is difficult for any of us to picture the distance, within the human brain, that human beings can gain from emotions that feel unsafe. Here I can’t help seeing this distance illustrated in physical distance between a parent and the vulnerable needs of their infant – measure in thousands of feet above the earth.

Bogart with fourth wife Lauren Bacall and their son, Stephen

A number of friends and colleagues were struck by Bogart’s emotional distance from his children. Screenwriter Adolphe Green spent time with Bogart with his children and said, “He was looking at [his] children as objects of curiosity, as if he had never seen children. As if to say, ‘who are these people? What are you?’ I’ll never forget that.”1 Bogart never ate with the children and once said “what do you do with a kid? They don’t drink.”1

So how was Bogart with adults? His son, having researched his father, said that “from the viewpoint of the Hollywood establishment, my father was widely regarded as a social misfit, and I think he liked it that way”1. I am curious about this statement, because the same was said of others who rose to become icons. Notably, Elvis Presley, John Lennon, Tupac Shakur and Marlon Brando were all described in this way, before their ‘misfitting’ persona became assumed to be part of an act – or just the eccentricity born of success. I’ve come to the conclusion that fame is often a way to live in persona – a way to meet a need for this distance from the real emotional self that was there all along.

As Bogart’s career developed, the characters he played smiled less and less. And the less they smiled, the more alluring and magnetic his performance became, reaching a pinnacle in Casablanca’s Rick Blaine. But his adult son had something to say about this ‘Mr Cool’ character with the raspy voice and the slight lisp: “Rick was but a minor variation on a role Bogart had himself been playing most of his adult life.” 1 This character was a version of a persona Bogart had developed for himself.

We often learn to see great actors as confident people who know themselves. But Bogart’s adult son said of his father, “Though famous for “speaking his mind” I don’t think he let his true feelings out to anybody ...All that mischief was a kind of mask.” 1 When Stephen had grown up he identified in himself an ability he thought he had got from Humphrey: the ability to “detach myself from my feelings”.1 Much of Bogart’s movie appeal to women, seemed to come from the fact that he didn’t need them. Bogart’s fourth wife Lauren Bacall said, “I think when he married me, Bogie thought I would be, like his other wives, a companion to his semi-bachelor existence.”1

Human beings who have a pattern of difficult childhood experiences with vulnerability can become able to disconnect from particular emotions – usually those that connect with vulnerability and dependency. This internal ability can be assisted with other more external strategies. If Bogart needed this distance from vulnerability, then he used both alcohol and sexual encounters as strategies to achieve this. He was found through his 20’s in the illegal gin joints of Manhattan. At the age of 50, he said “the whole world is three drinks behind. If everybody in the world would take three drinks, we would have no trouble.” 1 Together with an emphasis on performance and some lone intellectually biased activities (Bogart was a chess master and an avid reader), this begins to look like a lifestyle. In turn, these restrictions may impact the kind of people Bogart could get together with or marry. He perhaps needed the other to play an emotionally vulnerable role.

This situation could lead to a problem: If Hollywood is a magnet for people, with a similar profile to Bogart, who need the other to be emotionally vulnerable – how does Bogart find a partner in life? Across the rest of the world, there are billions who are comfortable enough being vulnerable. But Bogart is not surrounded by them, and perhaps, in any case, he can’t bear to be close to ordinary vulnerability. His children learned that. And so this is one reason why relationships between actors can appear complicated. In 1938, Bogart married his third wife, actress Mayo Methot. He liked to think of their marriage expectations as realistic, saying “Illusions are no good in marriage. And I love a good fight. So does Mayo."1 And Mayo did. One day actor friend Sam Jeffe took a call from Bogart.

“We have a problem” Bogart said.

“What’s the matter?”

“I think you’d better come over here.”

“Why?

“Mayo stabbed me”

When help arrived, Mayo was shouting “I didn’t do anything!” But Bogart was lying on the floor, just regaining consciousness after passing out. His jacket was covered with blood and a knife was in his back. The visiting doctor was bribed to keep this private1. Later in this relationship, there will be a shooting incident, with Bogart hiding in the bathroom.

We get used to hearing stories about celebrities that would be shocking if they occurred closer to home. Why should being a good actor necessarily put you in this kind of situation? Narcissism theory implies that both the acting and the complicated relationships are symptoms of the same childhood experiences which provoke a need for both emotional distance and idealisation. These domestic scenes paint Mayo, perhaps unfairly, as the ‘emotional’ ‘crazy’ ‘aggressive’ one. But then, perhaps this was by design. Bogart was the one who was specifically not being condemned or seen as emotionally vulnerable. He was on the other side. It was just like the role that cemented his acting ability in The Maltese Falcon. Why would he wish to avoid these specific roles in himself – a strategy that just happened to hold the keys to his iconic status - in his real life?

Rick Blaine with pianist Sam (played by drummer Dooley Wilson) in Casablanca (1942)

The shame game

On the map of narcissism is the use of devaluation of others as an adult strategy. It sits alongside performance and emotional distance. Devaluation can look like shaming or condemning others. This can be part of the grandiosity associated with narcissism. The emotional experience achieved with this strategy might be a powerful one attached to superiority – far from the shame or humiliation provoked in the other. In addition to his cold persona, lack of empathy and drive to perform, did he use this strategy more than others? One clue is that Bogart himself said, “People are afraid to invite me to their homes. They’re afraid that I will say something…”1 Director John Huston, said Bogart was known for “sticking in the saber.”3

Bogart would say to Rock Hudson “what kind of a name is that? What is ‘Rock Hudson’?”1 On a boat trip with his famous friends, actor Richard Burton described Bogart as “unnecessarily cruel”1 to an out of work singer called Frank Sinatra. He often hurt people with his “cutting remarks”1. There are many examples.

It is unusual for people to be criticised at their own funeral. It is a time for celebrating the good qualities that will be missed. Bogart at his funeral was remembered as one of the greatest actors in the Hollywood community. But he was also remembered for verbally denigrating those around him. Part of his eulogy read: “In each of the fountains of Versailles there is a pike which keeps all the carp active, otherwise they would grow fat and die. Bogie took rare delight in performing a similar duty in the fountains of Hollywood”1. It seems everyone knew what this was referring to.

So, alongside the performing qualities Bogart became famous for, there were strong patterns of emotional distance and the use of judgment and condemnation of others, the latter being described at his funeral. Did this man grow up with these personality features despite a good start in life? Did he just lack direction and a moral compass and drift before falling into acting through family connections? In part B, I will look at whether there were aspects of this comfortable upbringing that were so uncomfortable that they had a part to play in his iconic status today as an actor.

Bogart with wife Lauren Bacall and Marilyn Monroe

Disclaimer: All views expressed are my own unless otherwise stated, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution I have been employed by. The content here is for information and should not be interpreted as advice.

*Ryle did not apply this approach only to narcissism. If this mapping approach has been used in your own therapy, this does not mean that you have narcissistic difficulties.

Notes

1. Bogart, S. (1996). Bogart: In Search of my Father. Pan Books

2. Ryle, A. & Kerr, I.B. (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Wiley.

3. Porter, D. (2003). The Secret Life of Humphrey Bogart. Georgia Literary Association.

I wonder if the worship of celebrities is a projection of the narcissist’s need to be worshipped themselves?

Thank you for a fascinating article.